“The Pleasure of Vexing and Soothing”: The Subversive and Transgressive Power of Jane Eyre’s Erotic Pendulum

Since its 1847 publication, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre has blossomed forth as a garden of thorns and roses, igniting an enduring debate over whether the novel charts a proto-feminist trajectory of liberation or remains tethered to the very patriarchal chains it seeks to shatter. At the heart of this impassioned discourse lies its enigmatic and unsettling erotics, enmeshing readers and critics alike in its Gothic web of pain and love, dominance and submission, and labyrinthine psychosexual dynamics. Infused with sadomasochistic tensions of power, Jane Eyre channels the sublime interplay and uncanny dissolutions of normative boundaries characteristic of the Gothic to forge a radically transgressive erotics of power. Within the mysterious and murky recesses of the Gothic tradition, heroines like Jane Eyre embody disconcerting dualities and distinctive demeanors that infuse their desires with dissonance and their loves with disquiet as their narratives teeter on the precipice between liberation and constraint, and they frolic in the darkness.

Sexuality, desire, and love in the Gothic tradition are often unfurled as knotted webs of despair, fatalistic passion, and sadomasochistic perversion, prompting feminist critics such as Michelle A. Massé to denounce the genre as one where women “seeking recognition or love, learn to forget or deny that they also wanted independence and agency,” ultimately “internaliz[ing] and replicat[ing] the dynamics of oppression” through masochistic submission (Massé 3-4). As a Gothic tale that foregrounds a woman marching toward liberation while entangled in a complex love affair interlaced with pain and pleasure, dominance and submission, and patriarchal undercurrents, Jane Eyre is no stranger to these critiques. While many critics acknowledge the incandescent erotic flame that flickers in Brontë’s narrative heart, they disparage it as an “immature daydream” that reproduces “the asymmetrical power structures of the patriarchal family” (Mitchelle 44; Wyatt 201). Echoing Massé’s disapproval of Gothic masochism, Bette London critiques the novel’s narrative arc, asserting that “instead of the exhilaration of freedom, the novel offers the pleasures of submission,” tracing Jane’s journey as “a movement not from bondage to freedom but through increasingly powerful and interiorized forms of discipline” (London 199-200). Similarly, Anthony Michael D’Agostino identifies “Jane’s desire for Rochester” as a desire to be like Rochester, situating the novel’s sadomasochistic undercurrents as a means of constructing “a new self through the integration of the other’s desired traits” (D’Agostino 158). Yet, diverging from London, D’Agostino reframes Jane’s “assimilation to Rochester” not as a capitulation but as a reimagining of submission as “ the apotheosis of power itself” (D’Agostino 167). On the other end of the spectrum, scholars such as Mary Ann Davis have described Jane Eyre’s erotics as a “strategic erotics,” operating through sadomasochism’s “erotics of form” to articulate “an interdependent relationship between erotic power dynamics, female agency, and xenophobic and colonial rhetorics” (Mary Ann Davis 120). Feminist Victorian scholar Sandra M. Gilbert underscores the novel’s radical potential, describing its erotics as a “furious lovemaking,” a fiery “yearning not just for political equality but for equality of desire,” locating the novel’s subversive power in Jane’s “hunger, rebellion and rage” (Gilbert 357).

Unlike the Feminist critics who seek to “escape from the Gothic labyrinth,” Brontë integrates the proto-feminist narrative architecture into the confining spaces and murky atmospheres of the Gothic structures themselves (Massé 10). Within this labyrinth, each Gothic space serves as a symbolic topography mapping Jane’s evolution, charting her “process of becoming” while tracing it through the transgressive circuits of her eroticism (Nyman 147). The Gothic labyrinth of Jane Eyre unwinds inextricably entwined with its erotics, where untangling its knots and kinks unravels the text’s subversive power. Whereas for Davis, “multiple social rhetorics…produce her erotic agency,” and for Gilbert, it flares from a fierce rebellious sexual fervor, the merging of pain and desire that surfaces in the red-room and resurfaces in the liminal thresholds of Thornfield Hall exposes Jane Eyre’s erotics as a dialectical interplay of sadism and masochism (Davis 121). In contrast to D’Agostino’s vision of self-other fusion, the interplay of gazes and reconfigured power dynamics that culminate at Ferndean expose the novel’s ability to fracture the patriarchal hegemony it allegedly reproduces. This evolution begins in the red-room, where dominance and submission form a dialectic, later metamorphosing into a charged erotic interplay within the liminal spaces of Thornfield Hall and, ultimately, within the barren vacancy of Ferndean, transfiguring into a reciprocal love and equilibrating eroticism. The thorns and roses that blossom within the botanical bosom of Jane Eyre are not antagonistic but mutualistic: it is from “the pleasure of vexing and soothing” that Jane constructs her erotic desire, reconstructs her trauma and agency, and deconstructs her patriarchal subjugation (Brontë 183). Contrary to Massé’s notion of the Gothic as a “nightmare” of female entrapment, Brontë entwines the Gothic’s labyrinthine structures with the proto-feminist yearnings of her heroine, unraveling both the transgressive potential of female desire and the subversive power of the female Gothic.

From the opening pages of Jane Eyre, the red-room casts its spectral shadow as a primordial locus – a Gothic womb where the seeds of Jane’s lifelong negotiation with power, submission, and desire are sown. If the early chapters reveal Jane’s “two central longings – to be independent and to be loved,” the prominence of the red-room in her narrative suggests the emergence of a third longing: the desire to reconcile freedom with servitude (Yeazell 129). Imbued with “the mood of the revolted slave… still bracing [her] with its bitter vigor,” Jane laments: “Why was I always suffering, always browbeaten, always accused, for ever condemned? Why could I never please?” (Brontë 18). This paradoxical self-portrait of a “revolted slave” yearning to please unveils the dualistic desire pulsing within her heart – a longing for “freedom” paradoxically intertwined with “servitude,” as later articulated at Lowood in her desperate entreaty: “I desired liberty; for liberty I gasped; for liberty I uttered a prayer … ‘grant me at least a new servitude!’” (Brontë 102). Jane herself encapsulates this paradoxical puzzle as she reflects on her relationships with Mr. Rochester and St. John Rivers, framing her lifelong struggle as a pendulous oscillation, swinging incessantly between rebellion and submission:

I know no medium: I never in my life have known any medium in my dealings with positive, hard characters, antagonistic to my own, between absolute submission and determined revolt. I have always faithfully observed the one, up to the very moment of bursting, sometimes with volcanic vehemence, into the other; and as neither present circumstances warranted, nor my present mood inclined me to mutiny, I observed careful obedience. (Brontë 462)

The pendulum of desire, ceaselessly swaying between “absolute submission and determined revolt,” bursting “with volcanic vehemence” into one another, reflects a tremulous desire that reverberates through her psyche, rooted in the red-room. As Davies observes, this flux “characterizes later significant domestic spaces” and is birthed in the “violent dynamic of crimson and white, intimating blood, erotic love, and death” that materializes in the red-room (Davies 545).

In his essay “In the Window-Seat: Vision and Power in Jane Eyre,” Peter Bellis observes how Jane’s nascent longing for independence manifests as a yearning for visual power. Bellis contends that the early scenes at Gateshead “establish a pattern that the text will revise and ultimately reverse: Jane withdraws into a marginal spectatorship, only to be drawn out and exposed by an authoritative male gaze whose power is asserted through a culminating deprivation of vision” (Bellis 640). This dynamic is first magnified in Jane’s retreat to the window-seat, a “transitional space” where “her subjectivity is infused by possibility” (Nyman 146). Crouched in this space, she fantasizes about flying like a bird and gazing freely upon the earth – a fleeting daydream of autonomy that abruptly shatters when she refuses to acknowledge John Reed as her master and defiantly exclaims: “Master! How is he my master? Am I a servant?’” (Brontë 15). Her rebellion against John Reed provokes a patriarchal punishment enacted through the matriarchal agent, Mrs. Reed, who cruelly banishes her to the red-room. This morbid chamber, where her Uncle John Reed “breathed his last” breath, is described as “chill, because it seldom had a fire … silent, because [it was] remote,” and “solemn because it was known to be so seldom entered” (Brontë 17). The room’s blood-red and mahogany furnishings – its “bed supported on massive pillars of mahogany,” the table “covered with a crimson cloth, and the “darkly polished mahogany” chairs – evoke the “vacant majesty” of an empty tomb, charged with an eerie, hellish eroticism (Brontë 17). Imprisoned within the red-room’s “massive pillars of mahogany” and “curtains of deep red damask,” Jane is entombed in a space where death, punishment, and the shadow of her uncle’s patriarchal legacy intertwine with subtle erotic undercurrents (Brontë 17). These furnishings, simultaneously forbidding and sensuous, symbolize the grave of Jane’s autonomy while embedding the dynamics of punishment and pleasure into her psyche, forming a lifelong dialectic between rebellion and submission that reverberates within her relationships and suffuses the domestic and transitional spaces she roams.

As punishment for “the look [she] had in her eyes” – a gaze symbolizing her longing for independence – Mrs. Reed, as an agent of patriarchal subjugation, strips Jane of her all external vision by confining her to the red-room, where the window blinds are “always drawn down” (Brontë 17). Within this Gothic chamber, Jane’s only visual outlet is mediated through “subdued, broken reflections” in the wardrobe, the “muffled windows,” and a foreboding and illusory “great looking glass” (Brontë 17). The room itself is imbued with symbolic representations of authority, evoking through descriptors like “tabernacle” and “pale throne,” which summon what Hanly describes as a “traumatic and sadomasochistic œpidal fantasy,” wherein Jane imagines the spectral paternal energy of her deceased uncle as both punisher and avenger against the matriarchal tyranny of Mrs. Reed (Hanly 1052). In her attempt to reclaim some semblance of her dispossessed visual power, Jane fixes her “fascinated eye towards the dimly gleaming mirror,” only to encounter a distorted vision of herself as a “strange little figure” from one of Bessie’s fairy tales – ” a “tiny phantom” seemingly returned to haunt the Reed family (Brontë 18). This spectral image that casts her as both victim and avenger catalyzes the traumatic rupture that reverberates throughout the narrative. The traumatic weight of this event overwhelms her, leading her to feel “oppressed, suffocated … endurance broke down,” culminating in a “wild, involuntary cry” that shatters the oppressive silence of the household (Brontë 21). However, her defiance is swiftly punished as Mrs. Reed “abruptly thrusts [her] back and locked [her] in,” leaving Jane to spiral into a “species of fit” that provokes a loss of consciousness (Brontë 22). Yet paradoxically, the Gothic chamber’s punitive confinement becomes the crucible for Jane’s resistance. The red-room initiates Jane’s recognition of the oppressive structures of pain and authority that govern her early life. Her anguish cry of “‘Unjust! – unjust’” becomes a catalyst, signaling what she describes as a “strange expedient to achieve escape from insupportable oppression” (Brontë 19). The red-room thus emerges as a site of simultaneous subjugation and resurrection, externalizing the dynamics of power and punishment that Jane will later confront and reconfigure within the shadowed corridors of Thornfield Hall and within the stark barrenness of Ferndean. The convergence of patriarchal subjugation, paternalistic vengeance and salvation, and the spectral interplay of pain and pleasure – as embodied in the red-room’s erotic crimson hues and tomb-like stillness – foreshadows “the darker aspects of her passion with Rochester later on,” intertwining dominance and submission, the punitive and the pleasurable, into the fabric of her desire (Hanly 1052).

As the next pivotal narrative space where Jane Eyre’s erotics of power unfurl, the shadowed corridors and secret chambers of Thornfield Hall emerge as both a microcosm of patriarchal dominance and a mutable arena. This liminal Gothic setting becomes the threshold where Jane transmutes the intertwined threads of trauma and desire she first encountered in the red-room into a subversive erotic interplay that destabilizes the very foundations of dominance. With its labyrinthine halls, sealed attic, and the looming presence of hidden horrors, Thornfield Hall embodies what Michelle A. Massé describes as “the Gothic nightmare,” a space steeped in female oppression and captivity. Yet, within these confines, Jane stages a sadomasochistic interplay that challenges and reconfigures power itself. Micki Nyman identifies Thornfield’s “thresholds or portal images” as symbolic of “transformative space[s]” imbued with imaginative and intuitive possibilities (Nyman 145). By crossing the “pair of gates” at Thornfield, Jane steps into a liminal zone, untethering herself from the rigid constraints at Gateshead and entering an intermediary space where she finds immense pleasure in her solitary wanderings, roaming “along the corridor…backwards and forwards, safe in the silence and solitude [that allows her] mind’s eye to dwell on whatever bright visions rose before it” (Brontë 129). This liminal solitude grants her an imaginative freedom where she creates and narrates “a tale that was never ended… quickened with all of incident, life, fire, feeling, that [she] desired and had not in [her] actual existence” (Brontë 126). Thorfield, as a Gothic threshold, becomes a labyrinth for her imagination to roam, enabling her to construct the “fire [that she] desires” (Brontë 129). As her nascent autonomy and subjectivity begin to bloom within these liminal spaces, she reflects that “all sorts of fancies bright and dark tenanted [her] mind,” leading to her revelation: “Women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts…they suffer from too rigid a restrained, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer” (Brontë 130). Michel Foucault’s theory of sexuality as “a part of our world freedom” and a “possibility for creative life” resonates as Jane’s imaginative autonomy and subversive erotics converge to articulate a vision of freedom from within the confines of Thornfield Hall (Foucault 163). In her nocturnal wanderings through the dim, serpentine hallways, the spiraling staircases that coil like a serpent, the tangled-ivy moonlit garden, and the warm, glowing hearth of the drawing room, Jane navigates the transitional space of Thornfield Hall as a site of latent erotic possibility, where “bright and dark” fancies pulse within her, waiting to emerge in what she later transforms as a transgressive and reciprocal erotics of power.

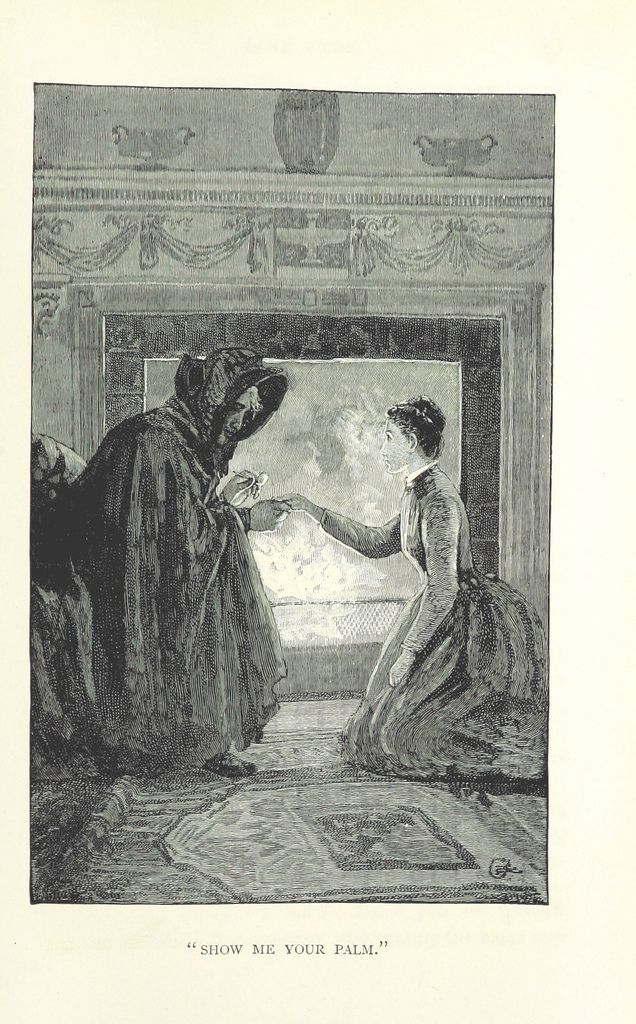

When Jane encounters Rochester at Hay Lane, the moment resonates with the spectral and paternal energies that haunted her in the red-room, reframing its imprisoning echos into the dynamic seeds of an erotic interplay. Arising like a phantom under a “moon waxing bright,” Rochester, along with his imposing “great lion-like” dog, is described as having a “dark face, with stern features, and a heavy brow,” an image doused with patriarchal authority that mirrors that phantasmal imagery of the red-room (Brontë 132). He glides forth from the shadows of dusk, incarnating a figure both enigmatic and authoritative that evokes Jane’s earlier memories of Bessie’s mythic tales, as she imagines him to be “a North-of-England spirit” which “sometimes came upon belated travellers, as this horse was now coming upon [her]” (Brontë 132). Yet, the dynamic between these elements is immediately more fluid and reciprocal than the fixed domination of the red-room, as Jane isn’t the only one who summons fantastic fairy tales and spectral imagery to describe this nocturnal moment. Rochester himself invokes the intangible mythic air of their encounter when he later tells Jane, “When you came on me in Hay Lane last night, I thought unaccountably of fairy tales and had half a mind to demand whether you had bewitched my horse” (Brontë 143). The moment at Hay Lane, therefore, subverts the red-room’s paradigm of dominance where Jane is silenced and cowers beneath patriarchal punishment and instead unfurls as its inversion; this time, it is Rochester who feels unsettled by an inexplicable bewitching essence and falls under the enchantment of Jane.

Rather than recoiling from his brusque and commanding demeanor, Jane appears enticed and enraptured by it, remarking, “Had he been a handsome, heroic-looking young gentleman, I should not have dared to stand thus questioning him against his will” (Brontë 134). The dominance and patriarchal authority he exudes paradoxically draws her closer, transforming it into an erotic seduction. She confesses the magnetic tension he arouses within her: “If he had put off my offer of assistance gaily and with thanks, I should have gone on my way … but the frown, the roughness of the traveller set me at my ease” (Brontë 134). Assuming the role of the commanding observer, she claims she “felt no fear of him” and yet oscillates between asserting and wielding, relinquishing and surrendering power – a shifting balance that exemplifies the nascent erotics of power that will come to define their relationship (Brontë 134). She instructs him to remain in place until she sees he is fit to mount his horse, yet when he orders her to grab the bridge, she obeys without hesitation, admitting, “I should have been afraid to touch a horse when alone, but when told to do it I was disposed to obey” (Brontë 134-5). She identifies two primary traits when she attempts to grasp the nature of his mysterious, enchanting aura: “firstly, because it was masculine; and, secondly, because it was dark, strong, and stern” (Brontë 136). The invocation of masculinity evokes the patriarchal specter reminiscent of the red-room, while his “dark, strong, and stern” features signify a shift away from childhood trauma toward a more complex, erotically charged desire. Unlike other authority figures in her life, Rochester’s dominance is marked by a playful oscillation that invites her into a flirtatious contest, an intoxicating dialectical game of power and submission where either player can win. The transformative encounter alters her perception of Thornfield, which now glimmers and glistens with desire; upon her return, she observes, “Thornfield Hall was a changed place,” finally imbued with the erotic desire she had long yearned for: “It had a master; for my part, I liked it better” (Brontë 139).

For Jane, the fanciful and fleeting allure of words like “Liberty, Excitement, Enjoyment,” which she describes as “delightful sounds truly, but no more than sounds,” ultimately resounds hollow, “so hollow and fleeting that it is a mere waste of time to listen to them” (Brontë 102). In contrast, she seizes the pragmatic appeal of “A new servitude! There is something in that…that must be a matter of fact,” a tangible framework that Rochester provides (Brontë 102). The tension between her yearning for liberty and her prayer for servitude is far less contradictory than it initially appears, as it is unraveled and reconciled continuously within the nuanced complexities of their erotic bond. For Jane, “servitude” transcends the idea of a static submission, becoming a mutable force, a fluid flux of power and desire capable of assuming a myriad of forms over the course of a lifetime – unlike the transient pleasures of “excitement” or “enjoyment.” Her inclusion of “Liberty” in this spectrum reflects her radical reimagining of it – not as an abstract, unattainable ideal, but as an active, sustained strategy that intertwines power and pleasure to offer her the potential of both. Rochester himself perceives this potency, remarking upon the “genuine contentment in [her] gait and mien, [her] eye and face, when [she is] helping [him] and pleasing [him],” which underscores how Jane derives erotic power from her acts of servitude (Brontë 250). This dynamic resonates with Michel Foucault’s assertion that sadomasochistic relationships embody “a perpetual novelty, a perpetual tension and a perpetual uncertainty, which the simple consummation of the act lacks” (Foucault 235). For a woman who “must have action” and cannot be “satisfied with tranquility,” someone who burns with desire for “fancies bright and dark,” the dialectical dynamic offers Jane an inexhaustible source of stimulation and fulfillment (Brontë 130). The ceaseless exchange fosters a sublime pleasure that resists stagnant stability, shielding her from “the viewless fetters of a uniform and too still existence” (Brontë 130).

From their initial interaction, Jane derives not only pleasure but also a profound sense of agency from serving Rochester. She reflects that she is “pleased to have done something” that, although momentary, “was yet an active thing,” emphasizing her rebellion against “an existence all passive” by reframing a supposedly subservient act as one imbued with intentionality and strategic agency (Brontë 136). As Margaret Ann Hanly observes, “Jane’s sexual love for Rochester is expressed through the imagery of slave and master,” a framework that she actively deploys because, unlike the despotic dominance of John Reed, who attempted to force her to call him “master” through sheer tyranny, Jane consciously and authoritatively chooses to serve Rochester on her own terms (Hanly 1052). From the moment she offers her service to assist his fall off his horse, she begins to exult this agency, eventually confessing: “I like to serve you sir and to obey you in all that is right” (Brontë 250). As their dynamic develops and deepens, Rochester discards conventional terms of endearment such as “love” and “darling” and instead adopts nicknames like “provoking puppet,” “malicious elf,” “sprite,” and “changeling,” each laden with playful provocation, and, more importantly, imply animacy (Brontë 315). These terms may appear imbued with sadistic undertones but resonate with Jane because they reject the inert passivity of a “beautiful doll” archetype in favor of fictions that possess vitality, intent, and mischief. Similarly, when Rochester’s “caresses” transform into “grimaces; for a pressure of the hand, a pinch on the arm; for a kiss on the cheek, a severe tweak of the ear,” Jane is not unsettled but rather pleased, asserting: “It was all right: at present I decidedly preferred these fierce favours to anything more tender” (Brontë 315). Through these moments, Jane illustrates her preference for these distortions of tenderness because, despite any sadistic tinge, they foreground her active participation in the dynamic while simultaneously arousing her erotic fire.

Jane’s surrender to Rochester is thus inextricably intertwined with an underlying sense of agency, revealing that at any moment, she maintains the capacity to refuse, revert, or subvert the very structures of their erotic architecture. When he boldly inquires whether she agrees he has “a right to be a little masterful, abrupt, perhaps exacting,” she immediately contests the claim (Brontë 157). Similarly, when he assertively commands her to speak, she disarms him with silence, “instead of speaking, [she] smiled,” a smile that she notes is “not a very complacent or submissive smile either” (Brontë 159). Their game of defiance and provocation continues as Rochester playfully yet menacingly warns her before their wedding: “It is your time now, little tyrant, but it will be mine presently…I’ll just – figuratively speaking – attach you to a chain like this” (Brontë 312). Disappointed by the “earnest, religious energy” in her tone and the “faith, truth, and devotion” in her gaze, he reveals to her the key to ignite his passion: “Look wicked, Jane: as you know well how to look: coin one of your wild, shy, provoking smiles; tell me you hate me — tease me, vex me; do anything but move me” (Brontë 325). Similarly, when he praises her as a “delicate and aërial beauty” with “fairy-like fingers,” she interrupts his romanticized rhetoric with astute defiance, exclaiming, “For God’s sake, don’t be ironical!” and commanding him to address her as his “plain, Quakerish governess,” rather than a whimsical ideal (Brontë 299). As their relationship evolves, Jane progressively unearths the intricacies of Rochester’s sadistic tendencies and their mutual desire for erotic transgression. She reflects: “I knew the pleasure of vexing and soothing him by turns; it was one I chiefly delighted in, and a sure instinct always prevented me from going too far; beyond the verge of provocation I never ventured; on the extreme brink I liked well to try my skill” (Brontë 183). This admission illuminates the back-and-forth dance of their bond, in which the two thrive on “the extreme brink” of teetering power. Jane discovers Rochester does not actually want her to be completely submissive any more than she actually wants to be unmitigatedly dominated, but instead, it is in their mutual negotiation of power that their erotic pleasure finds its most potent source.

As John Kucich observes, Jane and Rochester’s relationship is “always constituted as a battleground – but a battleground with power flowing alternately in two directions” (Kucich 932). This oscillating pendulum of power, “the reversibility of power relations” itself, generates their mutable pleasure and solidifies Jane’s agency and subjectivity (Kucich 931). For Jane, the significance of these master/slave oscillations lies in their capacity to “pluralize and confuse the configurations of power to such a degree that contest-which defines isolation and distance becomes endless and illimitable, rather than frozen in some kind of permanent structure of relationship,” inciting her to assert a liberation that is self-determined and never fixed (Kucich 934). Jane admits that Rochester’s gae “mastered [her]” and took her feelings “from [her] own power and fettered them into his,” yet Rochester similarly confessed: “I never met your likeness. Jane, you please me, and you master me—you seem to submit, and I like the sense of pliancy you impart; and while I am twining the soft, silken skein round my finger, it sends a thrill up my arm to my heart. I am influenced—conquered” (Brontë 203, 301). This intricate dans of domination and submission deny conventional power structures, creating instead what Kucich describes as an “atmosphere of combat and competition” where “no one is actually mastered” (Kucich 934). Instead, their dynamic operates within what Foucault terms “the eroticization of power, the eroticization of strategic relations” (Foucault 163). As Foucault elucidates, “Of course, there are roles, but everybody knows very well that those roles can be reversed. Sometimes the scene begins with the master and slave, and at the end, the slave has become the master” (Brontë 169). Jane Eyre and Rochester’s bond thrives precisely because of this irreversibility and instability. In sark contrast, St. John embodies a rigid, oppressive authority that extinguishes the very flame igniting her existence. She recognizes that by marrying him, he would control her entirely, subjecting her to constant physical and emotional confinement and constraints, where she would suffer as “attached to him only in this capacity: my body would be under rather a stringent yoke, but my heart and mind would be free,” but only in so far as it is “forced to keep the fire of [her]nature continually low, to compel it to burn inwardly and never utter a cry, though the imprisoned flame consumed vital,” and that, above all else, is what “would be unendurable” (Brontë 470). For Jane, “fire of her nature” is not merely a metaphor for her passion but the very medium from which she configures, conceptualizes, discovers, and articulates her selfhood, eroticism, and freedom. As she wars, joining him would completely annihilate her subjectivity: “I abandon half myself,” reflecting that, if he dims or extinguishes her flicker, she will inevitably “go to premature death” (Brontë 466).

When Thornfield erupts into flames, it dismantles not only the ensnaring spatial confines of its patriarchal corridors but also ignites a symbolic purging of the suffocating structures that have long repressed Jane’s agency and concealed her erotic, visual, and narrative power. As Sandra Gilbert asserts, “many critics… have seen Rochester’s injuries as a symbolic castration,” yet this castration signifies not merely the diminishment of Rochester’s patriarchal power but a profound erotic reconfiguration where Jane assumes visual authority and spectatorship, transforming her subjugation in the red-room into a mutualistic vantage point (Gilbert 802). The flames that devour Thornfield not only annihilate the mansion’s physical edifice but dissolve the social, material, and corporeal privileges that sustained Rochester’s dominance, scorching his wealth and rendering him blind, positioning Jane as the arbiter of their newly formed role reversal. The fire’s wild, uncontrollable flames, like the hellish crimson of the red-room, carry an eroticized charge – disruptive and purgative – that mirrors the burning intensity of their passion and the scorching agency sprouting from Jane. The inferno at Thornfield allows Jane to reclaim the visual power and agency she lost in the crimson drapes of the red-room, and in doing so, fulfills her three central longings: independence, love, and a fiery, subversive, transgressive eroticism that resists Victorian constraints. Whereas Jane was once a bird caged within the red-room, her vision clipped and autonomy suffocated, Rochester becomes “the caged eagle, whose gold-ringed eyes cruelty has extinguished,” a reversal that empowers Jane as both seer and interpreter (Brontë 498). Rather than simply a destructive symbolic castration, the fire blazes forth as a redemptive recalibration.

From the ashes of Thornfield, Ferndean rises as the narrative apotheosis – a space of recalibration and relational renewal where the oscillating interplay of dominance and submission evolves into a symbiotic equilibrium. In stark contrast to the menacing and ominous Gothic grandeur of Thornfield, Ferndean is described as “a building of considerable antiquity, moderate size, and no architectural pretensions, deep buried in a wood,” its bare isolation and unadorned simplicity symbolizes a detachment from the economic and societal hierarchies that previously dictated and characterized Jane and Rochester’s dynamic (Brontë 496). Within the “uninhabited and unfurnished” voids of Ferndean, Jane finally heals from the suffocating trauma of the red-room and breaks away from the confines of Thornfield, while Rochester relinquishes his patriarchal dominance, allowing the pair to rearticulate their erotic bond unmediated by external constraints (Brontë 496). Yet, this inversion of power does not settle into stasis; Rochester’s blindness renders him dependent on Jane as “his vision” and “the apple of his eye” and reasserts her visual power and pleasure (Brontë 519). She asserts, “I will be your neighbour, your nurse, your housekeeper. I find you lonely: I will be your companion,” signaling a delicate equilibrium of agency and mutuality, maintaining both patriarchal reduction and the complete effacement of their previous roles (Brontë 519). When Jane invokes the phrase “my dear master,” she reinscribes the erotic tension within their recalibrated relationship, where power remains fluid and contestable. It is within Ferndean’s stripped-down simplicity, empty spaces, and vacancy that Brontë reconfigures the Gothic dialectic of dominance and submission into a mutualistic, subversive, and transgressive interplay Jane’s proclamation, “I am my husband’s life as fully as he is mine,” does not signify her capitulation to Victorian marital conventions, nor does her final substitution of “husband” for of “master” signify the dissolution of their erotic systems (Brontë 519). Instead, it marks their union as one forged through a sadomasochistic interplay of intimacy and transgressive, both mutualistic and defiantly transgressive (Brontë 519). Critics who contend that Jane Eyre remains rooted in the oppressive structures of dominance and submission are not entirely mistaken but often fail to grasp the unfathomable complexity of female eroticism and Gothic narrative subversion. The subversion of Bronte’s narrative is not about eradicating power but about transmuting it into a fluid, relational, and mutualistic framework that allows Jane to emerge not as an idealized Victorian woman nor as a conventional feminist icon, but as a transgressive Gothic heroine who forges her identity from the embers of her erotic passion. As the flames of Thornfield fade into the quiet isolation of Ferndean, the fire of the female erotic endures. Through Jane crumbles the Gothic walls that once confined her, Brontë’s narrative of thorns and roses, vexing and soothing, never truly ends, perpetually burning with potential.

Works Cited

Bellis, Peter J. “In the Window-Seat: Vision and Power in Jane Eyre.” ELH, vol. 54, no. 3, 1987, pp. 639–52, https://doi.org/10.2307/2873224.

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Edited by Stevie Davies, Penguin Classics, 2006.

Burke, Edmund, and David Womersley. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful : And Other Pre-Revolutionary Writings. Penguin Books, 1998.

D’Agostino, Anthony Michael. “Telepathy and Sadomasochism in Jane Eyre.” Victorians : A Journal of Culture and Literature, no. 130, 2016, pp. 156-169.

Davis, Mary Ann. “‘On the Extreme Brink’ with Charlotte Bronte: Revisiting Jane Eyre’s Erotics of Power.” Papers on Language & Literature, vol. 52, no. 2, 2016, pp. 115–48.

Gilbert, Sandra M. “Jane Eyre and the Secrets of Furious Lovemaking.” NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 31, no. 3, 1998, pp. 351–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1346105.

— “Plain Jane’s Progress.” Signs, vol. 2, no. 4, 1977, pp. 779–804. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173210.

Hanly, Margaret Ann. “Sado-Masochism in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre: A Ridge of Lighted Heath.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, vol. 74, no. 5, 1993, pp. 1049–61.

Kucich, John. “Passionate Reserve and Reserved Passion in the Works of Charlotte Brontë.” ELH, vol. 52, no. 4, 1985, pp. 913–37. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3039472.

London, Bette. “The Pleasures of Submission: Jane Eyre and the Production of the Text.” ELH, vol. 58, no. 1, 1991, pp. 195–213. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2873399.

Nyman, Micki. “Portals of Desire in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Fanny Fern’s Ruth Hall.” Brontë Studies : Journal of the Brontë Society, vol. 42, no. 2, 2017, pp. 143–53.

O’Higgins, James, and Michel Foucault. “Sexual Choice, Sexual Act: An Interview with Michel Foucault.” Salmagundi, no. 188/189, 2015, pp. 222–39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43942302. Accessed 16 Dec. 2024.

Yeazell, Ruth Bernard. “More True Than Real: Jane Eyre’s ‘Mysterious Summons.’” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 29, no. 2, 1974, pp. 127–43. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2933287.

Leave a comment